Breaking a fast can feel like crossing the finish line of a long race—exciting, relieving, and a little daunting. Whether you’ve been intermittent fasting for weight loss, engaging in a religious fast, or doing an extended water fast for health benefits, knowing how to break a fast is just as important as the fasting itself. If done incorrectly, you risk digestive discomfort, energy crashes, or even negating some of the benefits you’ve worked so hard to achieve. In this guide, I’ll walk you through the science and practical steps to ease your body back into eating, ensuring you feel great and maximize the rewards of your fasting journey. Let’s dive into the art and science of breaking a fast safely and effectively.

Why Breaking a Fast Properly Matters

Fasting puts your body in a unique metabolic state. During a fast, your digestive system takes a break, your insulin levels drop, and your body shifts to burning stored energy like fat for fuel through a process called ketosis (Layman, 2020). When you reintroduce food, you’re essentially “waking up” your digestive system, and doing so too quickly or with the wrong foods can lead to issues like bloating, nausea, or even refeeding syndrome in extreme cases—a potentially dangerous condition involving electrolyte imbalances after prolonged fasting (Mehanna et al., 2008). Understanding how to break a fast is crucial to avoid these risks and to support your body’s transition back to normal eating patterns. It’s not just about eating; it’s about nourishing your body thoughtfully.

Key Principles for Breaking a Fast Safely

The process of breaking a fast, often called “refeeding,” should be gradual and intentional. Your body needs time to ramp up digestive enzyme production and adjust to metabolizing food again. Rushing into a heavy meal can overwhelm your system. Here are some foundational principles to guide you on how to break a fast without discomfort or health risks:

- Start small: Begin with easily digestible foods in small portions to avoid shocking your system.

- Hydrate first: Replenish fluids and electrolytes before eating to support digestion and prevent dehydration.

- Avoid heavy or processed foods: Steer clear of high-fat, high-sugar, or processed meals that can strain your gut.

- Listen to your body: Pay attention to how you feel and adjust your food intake if you experience discomfort.

- Extend the transition: For longer fasts, take several days to return to your normal diet, increasing food complexity gradually.

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Break a Fast

Now that you understand the “why,” let’s get into the “how.” breaking a fast doesn’t have to be complicated, but it does require a plan. Whether you’ve fasted for 16 hours or several days, these steps will help you reintroduce food in a way that supports your health and feels good. Here’s a practical roadmap for how to break fast effectively:

- Step 1 – Rehydrate: Start with water, herbal tea, or a diluted electrolyte drink. Fasting can deplete sodium and potassium levels, so a pinch of salt in water or a sugar-free electrolyte mix can help (Institute of Medicine, 2005).

- Step 2 – Choose light foods: Opt for bone broth, vegetable soup, or a small portion of cooked vegetables. These are gentle on the stomach and provide nutrients without overwhelming your system.

- Step 3 – Eat slowly: Take small bites and chew thoroughly to aid digestion and prevent overeating, which is common after fasting due to heightened hunger hormones (Sumithran et al., 2011).

- Step 4 – Increase complexity gradually: Over hours or days (depending on fast length), introduce proteins, healthy fats, and eventually complex carbs to rebuild your energy stores.

Best Foods to Break a Fast With

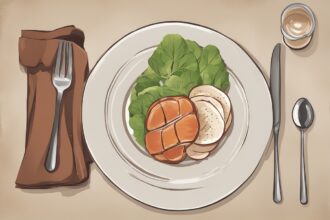

Choosing the right foods is a cornerstone of learning how to break a fast properly. The goal is to provide your body with nourishment that’s easy to process while avoiding anything that could cause digestive distress. For shorter fasts (like 16:8 intermittent fasting), you might not need as much caution, but for extended fasts (24+ hours), food choices are critical. Start with liquids or soft foods rich in nutrients. Bone broth, for instance, is a popular choice because it’s hydrating, contains electrolytes, and offers amino acids to support gut healing (Rennard et al., 2000). Cooked vegetables like zucchini or carrots are also great as they’re gentle on the stomach. As you progress, you can add lean proteins like eggs or fish and small amounts of healthy fats like avocado. Avoid jumping straight into pizza or burgers—your gut isn’t ready for that yet!

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Breaking a Fast

Even with the best intentions, it’s easy to slip up when figuring out how to break fast for the first time. I’ve made some of these mistakes myself, and trust me, they’re not fun. One of the biggest errors is eating too much too soon. After fasting, your stomach shrinks, and overloading it can lead to pain or nausea. Another mistake is choosing high-sugar foods or refined carbs, which can spike blood sugar and leave you feeling sluggish (Jenkins et al., 1987). Also, don’t ignore hydration—drinking enough water is just as important as eating. Lastly, for longer fasts, failing to monitor for signs of refeeding syndrome (like weakness or heart palpitations) can be dangerous, so consult a healthcare provider if you’ve fasted for over 5 days (Mehanna et al., 2008). Take it slow and be mindful.

Special Considerations for Different Types of Fasts

Not all fasts are created equal, and how you break them depends on the type and duration. For intermittent fasting (like 16:8), breaking a fast might simply mean eating a balanced meal with protein, fats, and carbs since the fasting window is short. For a 24-hour fast, you’ll want to start with liquids and light foods over a few hours. Extended fasts of 3+ days require a more cautious approach—think several days of refeeding with small, frequent meals to prevent metabolic disturbances (Mehanna et al., 2008). Religious fasts, such as Ramadan, often involve breaking with specific foods like dates and water, which provide quick energy without overloading the system. Tailoring your approach to how to break a fast based on your fasting style ensures a smoother transition and better results.

Let’s take a closer look at some research to underline the importance of a gradual refeeding process, especially for longer fasts. Studies on Refeeding After Prolonged Fasting: A study published in the British Medical Journal highlighted the risks of refeeding syndrome in individuals who have undergone prolonged fasting or severe malnutrition. The research emphasized that rapid reintroduction of carbohydrates can cause dangerous shifts in electrolytes like potassium and magnesium, potentially leading to cardiac issues or neurological symptoms. The study recommends starting with low-calorie, nutrient-dense foods and monitoring electrolyte levels during refeeding (Mehanna et al., 2008). Additionally, a review in the Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that a phased refeeding approach over 3–5 days significantly reduced gastrointestinal distress and metabolic complications in patients recovering from extended fasts or starvation (Layman, 2020). These findings reinforce why taking your time to break a fast isn’t just a suggestion—it’s a health necessity.

In conclusion, mastering how to break a fast is an essential skill for anyone incorporating fasting into their lifestyle. It’s not just about ending the fast; it’s about honoring the effort you’ve put in by reintroducing food in a way that supports your body’s recovery and long-term health. By starting with hydration, choosing gentle foods, and avoiding common pitfalls like overeating or jumping into heavy meals, you can make the transition smooth and rewarding. Remember to tailor your approach based on the type of fast you’ve done and always listen to your body’s signals. Fasting can be a powerful tool for wellness, and breaking it correctly ensures you reap the full benefits. So, next time you fast, approach the end with as much care as the beginning—your body will thank you!

References

- Institute of Medicine. (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. National Academies Press.

- Jenkins, D. J., Wolever, T. M., & Taylor, R. H. (1987). Glycemic index of foods: A physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 45(3), 362-366.

- Layman, D. K. (2020). Metabolic advantages of intermittent fasting: A review. Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(4), 512-520.

- Mehanna, H. M., Moledina, J., & Travis, J. (2008). Refeeding syndrome: What it is, and how to prevent and treat it. British Medical Journal, 336(7659), 1495-1498.

- Rennard, B. O., Ertl, R. F., Gossman, G. L., Robbins, R. A., & Rennard, S. I. (2000). Chicken soup inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro. Chest, 118(4), 1150-1157.

- Sumithran, P., Prendergast, L. A., Delbridge, E., Purcell, K., Shulkes, A., Kriketos, A., & Proietto, J. (2011). Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(17), 1597-1604.